Mount Kenya’s glaciers are vanishing rapidly – over 95% of their ice has disappeared since 1900, and they could be gone entirely before 2030. This loss is driven by climate change, rising temperatures, and reduced snowfall, threatening water supplies for over 2 million people in Kenya and Tanzania. Key points:

- Glacier Shrinkage: From 18 glaciers in 1900 to just 10 today, covering only 0.069 km².

- Impact on Water: Rivers like Naromoru and Ngare Ngare are seeing reduced flow, affecting agriculture and livelihoods.

- Cultural and Environmental Loss: Mount Kenya’s glaciers are vital for local communities and ecosystems.

The retreat of these glaciers highlights the urgent need for conservation and sustainable tourism efforts. Without action, this iconic natural feature will soon disappear.

The Geological Origins and Glacial History of Mount Kenya

Formation of Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya’s story began roughly 3 million years ago when the Earth’s crust fractured as part of the East African Rift System. During the Plio-Pleistocene era (3.1–2.6 million years ago), volcanic eruptions layered the mountain with basalt, rhomb porphyrites, and other rocks, eventually creating Africa’s second-highest peak. At its prime, Mount Kenya may have soared to 7,000 meters, with its original crater rising above 6,000 meters [1].

The central peaks – Batian, Nelion, and Lenana – are what remain of the mountain’s volcanic core. These hardened magma plugs have withstood millions of years of glacial erosion, while softer surrounding material was worn away by ice. These towering remnants are a striking reminder of Mount Kenya’s volcanic past.

Further volcanic activity on the mountain’s northeastern side added additional plugs and craters, enhancing its rugged and intricate profile [1]. This volcanic groundwork set the stage for the glacial forces that would later shape the mountain into its current dramatic form.

Major Glaciation Periods

Mount Kenya’s transformation from a massive volcanic cone to its current appearance was driven by multiple glaciation periods spanning millions of years. The earliest glacial activity is traced back to the Plio-Pleistocene boundary, around 2.47 million years ago [8], making it one of the longest-recorded glacial histories in tropical regions.

Researchers have identified two significant glaciation periods, marked by distinct moraine rings – deposits of rocky debris left behind as glaciers retreated. The lowest moraine, located at approximately 3,300 meters (10,800 feet), indicates the furthest extent of ice coverage during the mountain’s most extensive glacial phase [1].

Cosmogenic dating has pinpointed glaciation events at 28,000, 14,600, 10,200, and 8,600 years ago, with a smaller event occurring around 200 years ago. Evidence of glaciation also stretches back over 250,000 years [7].

Early researcher Gregory theorized that the summit was once entirely covered by an ice cap, which gradually eroded the peaks into their current jagged shapes [1]. This colossal ice sheet carved out the U-shaped valleys now visible in the moorland zones, while the lower slopes, untouched by glaciers, still feature V-shaped valleys formed by water erosion [1].

Over time, repeated cycles of ice advancement and retreat sculpted Mount Kenya’s dramatic landscape. U-shaped valleys deepened, ridges sharpened, and volcanic plugs were exposed, giving rise to the rugged peaks that challenge climbers today. In the higher elevations, glacial deposits offer a clear record of these cycles, illustrating the mountain’s dynamic history [9].

These ancient glacial processes not only shaped Mount Kenya’s striking terrain but also played a key role in forming its iconic peaks and climbing routes. Understanding these cycles helps provide insight into the mountain’s past and its ongoing changes.

The Current State of Mount Kenya’s Glaciers

Retreat of Mount Kenya’s Glaciers

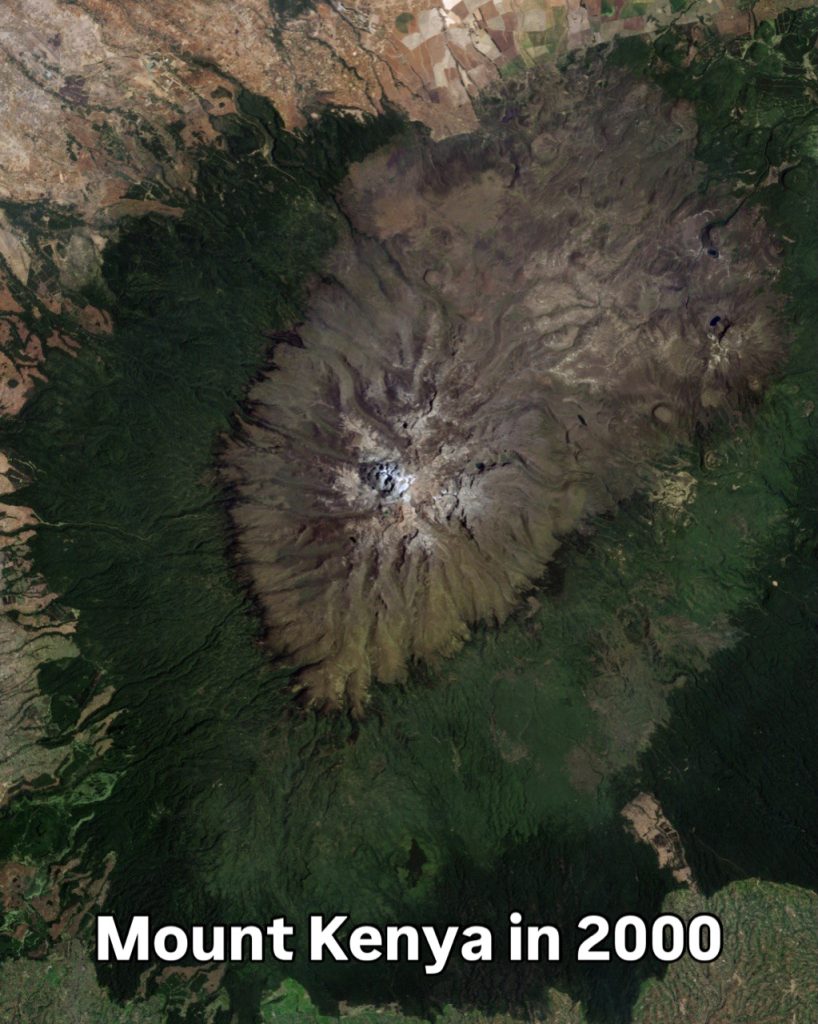

Mount Kenya, once crowned with extensive glacial coverage, is now witnessing a dramatic decline in its ice. A century ago, 18 glaciers adorned the summit; today, only 10 remain[6]. This sharp reduction is one of the most extreme examples of glacier retreat in tropical regions.

A 2024 satellite study reveals that Mount Kenya has lost over 95% of its glacial area since 1900. What’s left now amounts to just 0.069 km² of ice, or 4.2% of its original size compared to the first reliable measurements taken in 1900[3][4].

The Lewis Glacier, once spanning 0.6 km² in the early 20th century, has undergone severe shrinkage. Between 1934 and 2010, it lost 90% of its volume, and in just five years, its size dropped by 62%[3][4][11]. More recently, between 2014 and 2016, the Nothey and Darwin glaciers vanished altogether, while the Lewis Glacier fragmented into two separate ice masses[4]. This fragmentation signals an advanced stage of retreat, as continuous ice sheets break apart under the strain of warming temperatures. The pace of glacial loss has quickened over the past two decades, with particularly sharp declines recorded since 2016[4][10]. Today, Mount Kenya holds the grim title of having the smallest remaining glacier area in East Africa[4].

These alarming changes set the foundation for understanding the climate-related forces driving this retreat.

Impact of Climate Change

The retreat of Mount Kenya’s glaciers is a direct consequence of climate change, driven by rising global temperatures, reduced precipitation, and deforestation[11]. These factors work together, accelerating the loss of ice on the mountain.

Changes in ocean temperatures also play a significant role. Rainer Prinz from the University of Innsbruck in Austria highlights how surface temperature shifts in the Indian Ocean disrupt moisture transport across East Africa. This disruption reduces snowfall, which acts as a protective layer for the glaciers[3].

“If they don’t have that, they will just melt away”[3].

Projections are grim. Some scientists warn that Mount Kenya could lose all its ice by 2030, while others suggest the glaciers might disappear entirely by 2044 if warming trends continue[3][6].

This loss has far-reaching consequences. Over 66% of residents along the Naromoru River report reduced water flow, and the Ngare Ngare River has seen a 30% drop in water levels over the last decade[4]. These changes threaten an ecosystem that supports over 2 million people[12]. Farmers and herders, who depend on this water, are increasingly facing challenges to their livelihoods, sometimes leading to violent conflicts over dwindling resources[6]. Additionally, Mount Kenya’s glaciers are vital to two major rivers – the Tana River and the Ewaso Ng’iro North – making their survival crucial for regional water security[12].

For trekkers and climbers, the rapidly changing landscape of Mount Kenya’s glaciers underscores the urgency of visiting while they still exist. Local operators like Wild Springs Adventures (https://wildsprings.co.ke) provide expert guidance, ensuring visitors can explore these ancient ice formations responsibly. By promoting sustainable tourism, such efforts help preserve not only the mountain’s fragile environment but also its importance as a natural and cultural landmark.

Glaciers and Peaks: Key Features of Mount Kenya

Lewis and Tyndall Glaciers

Mount Kenya’s iconic glaciers, Lewis and Tyndall, are among the last remnants of the mountain’s icy past, but they are rapidly disappearing. These glaciers, vital for the mountain’s ecosystem, have dramatically shrunk since the Little Ice Age.

The Lewis Glacier, once the largest and most prominent, has faced a staggering reduction. Between 1934 and 2018, its area dropped from 0.49 km² to a mere 0.04 km². During the Little Ice Age, the glacier spanned 0.678 km², while the Tyndall-I glacier system covered 0.390 km². Since then, the glaciers have lost 87.0% and 88.7% of their size, respectively.

Recent studies paint an even grimmer picture. From 2004 to 2016, the Lewis Glacier shed 46% of its surface area and 57% of its volume. By 2024, only 10% of its 1980s surface area remained – about 6.9 hectares, roughly half of what was recorded in 2016. The glacier is now splitting into two due to a rock outcrop, signaling its advanced deterioration.

The Tyndall Glacier faces similar struggles, clinging to high-altitude terrain as it contends with rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns. These shrinking glaciers frame Mount Kenya’s rugged peaks, highlighting the constant interplay between ice and rock in this dramatic landscape.

Major Peaks: Batian, Nelion, and Lenana

Mount Kenya’s towering peaks – Batian, Nelion, and Point Lenana – each offer unique challenges and breathtaking views of the glaciers.

Batian, the highest peak at 5,199 meters (17,057 feet), is the most demanding climb. Scaling this technical summit requires advanced mountaineering skills, and only about 50 climbers make it to the top each year. Its proximity to the glaciers makes it a critical spot for studying ice retreat and climate change.

Nelion, standing at 5,188 meters (17,021 feet), is the second-highest peak and equally challenging. Together, Batian and Nelion are often referred to as the “Gates of Mist” due to their dramatic appearance and frequent cloud cover. The glaciers, including the Lewis Glacier, nestle among these peaks, creating a striking contrast of ice against rock.

Point Lenana, at 4,985 meters (16,355 feet), offers a more accessible adventure. Unlike its technical counterparts, Lenana can be reached without specialized climbing skills, making it a favorite for trekkers seeking a rewarding summit experience.

UNESCO describes Mount Kenya as featuring “rugged glacier-clad summits”, a defining characteristic of one of East Africa’s most stunning landscapes. Compared to Kilimanjaro, Mount Kenya retains a more substantial glacier presence, though this is rapidly changing. Scientists predict that the glaciers could vanish entirely before 2030, emphasizing the urgency of witnessing these ancient ice formations while they still exist.

The best times to climb and experience the peaks and glaciers are January, February, early March, and August. Conditions from September through December can also be favorable. Beyond their allure for climbers, these peaks serve as invaluable natural laboratories. The glaciers around Batian and Nelion capture climate data from the tropical mid-troposphere, offering critical insights into global warming’s effects in equatorial regions, where glacier retreat is occurring faster than the global average.

As the landscape evolves, it not only shapes climbing experiences but also highlights the need for sustainable tourism. Local operators, such as Wild Springs Adventures (https://wildsprings.co.ke), now incorporate the latest climate research into their expedition planning, ensuring safer and more informed climbs.

Conservation, Tourism, and Local Involvement

Tourism Practices for Conservation

With Mount Kenya’s glaciers rapidly disappearing, conservation efforts have become more urgent than ever. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, this mountain relies on responsible tourism to ensure its ecosystems remain intact for future generations.

Sustainable tourism is reshaping how visitors experience Mount Kenya. Hosting around 20,000 visitors annually [13], the mountain generates economic benefits that can support conservation efforts – if managed carefully. To protect these fragile ecosystems, eco-friendly accommodations have become the norm. These lodgings focus on conserving water, reducing waste, and using renewable energy, offering visitors a comfortable and environmentally conscious base for activities like glacier viewing and peak climbing. Additionally, everyone is encouraged to follow the “Leave No Trace” principles, ensuring minimal impact on the environment.

Sustainable tourism also emphasizes cultural connections, helping visitors understand Mount Kenya’s deep spiritual significance to local communities. As Mwangi Gitaru explains:

“He believed the mountain was the source of life… We were told as young boys, that was where the gods were. And we believed it.”

This cultural immersion not only enriches the visitor experience but also highlights the importance of preserving the mountain for both its natural and spiritual value.

Another key aspect of responsible tourism is wildlife viewing. Mount Kenya’s forests, which provide ecosystem services estimated at $220 annually [13], are home to diverse species, including the endangered Mountain Bongo. By observing wildlife responsibly and avoiding habitat disruption, visitors play a role in maintaining the delicate ecosystems that sustain both animals and local communities.

Sustainable practices like these, combined with strong local partnerships, are paving the way for more effective conservation efforts on Mount Kenya.

Local Partnerships and Guides

Conservation on Mount Kenya thrives through partnerships that bring together local communities, tourism operators, and conservation groups. One standout example is Wild Springs Adventures (https://wildsprings.co.ke), a Nairobi-based company that collaborates with local guides, porters, and nearby communities to promote responsible tourism and conservation.

The Mount Kenya Trust (MKT) is another key player, working alongside the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), local communities, and private operators to protect 271,338 hectares of forest. This collaborative model has positively impacted 2,000 community members [15], showcasing how conservation and community support can go hand in hand.

Community conservancies around Mount Kenya empower locals to manage their natural resources. These initiatives use funds from ecotourism to support education, healthcare, and environmental programs. Across Kenya, more than 160 community conservancies now exist, with 65% of the country’s wildlife living outside government-protected areas [14]. This approach demonstrates how locals can take ownership of conservation while benefiting economically.

Certified guides and porters also play a vital role by offering visitors authentic experiences and sharing insights about the mountain’s natural and cultural significance. Their involvement not only enhances visitor understanding but also creates economic incentives to protect Mount Kenya’s unique environment.

Grassroots efforts like those led by the Mt. Kenya Biodiversity Conservation Group (Mt. KEBIO) further highlight the power of local action. In 2023, the group organized 12 bird walks, participated in Global Big Days, distributed 7,400 tree seedlings to schools and communities, and worked on restoring the Nanyuki River. These initiatives demonstrate how local engagement can directly sustain ecosystems vital to Mount Kenya’s glaciers [13].

Larger-scale efforts, such as those by the Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT), amplify these successes. Since its founding in 2004, the NRT has supported community conservancies covering over 63,000 square kilometers in northern Kenya. This approach not only protects vast landscapes but also provides sustainable livelihoods for local populations [14].

Through these collaborative efforts, tourism transforms into a force for good. Local operators like Wild Springs Adventures connect international visitors with conservation initiatives, ensuring that every visit contributes to preserving Mount Kenya’s glaciers and ecosystems for generations to come.

Conclusion: The Future of Mount Kenya’s Glaciers

Key Takeaways

Mount Kenya’s glaciers are a stark reminder of the sweeping environmental changes reshaping ecosystems worldwide. Since 1900, the mountain has lost an astonishing 95% of its glacier area, mirroring the broader trend of Africa’s tropical glaciers shrinking by 90% over the same period [16][4]. Today, only 10 of the original 18 glaciers remain [5].

The Lewis Glacier, in particular, highlights the severity of this decline. Since 1934, it has lost 90% of its volume, with 46% of its area disappearing between 2004 and 2016 [5][2]. Even more concerning, the annual retreat rate has accelerated – from 0.8% per year (1947–1963) to 3.8% (2004–2016) [2].

The primary driver behind this retreat is climate change, marked by rising temperatures, reduced snowfall, and declining cloud cover [16]. Anne Hinzmann, lead author of a study in Environmental Research: Climate, emphasizes the gravity of the situation:

“A decrease at this scale is alarming. The glaciers in Africa are a clear indicator of the impact of climate change.” [16]

This isn’t just about ice. Water levels in the Ngare Ngare River have dropped by 30% over the past decade [17], and 66% of residents along the Naromoru River report reduced downstream flow [4]. If current trends continue, projections suggest Mount Kenya’s glaciers could vanish entirely before 2030 [2]. The loss would not only be an environmental disaster but also a profound cultural blow for communities that hold the mountain sacred.

Call to Action for Awareness and Conservation

The urgency is clear: action is needed on both local and global levels to address these challenges. As Isaac Kalua poignantly notes:

“We cannot do anything about it. It is not our problem. We are not responsible for the massive emissions responsible for global glacial melts. But we are suffering the consequences.” [5]

Despite this, there are ways to make a difference. Sustainable tourism offers a direct way to support conservation. Companies like Wild Springs Adventures demonstrate how tourism operators can collaborate with local communities to create economic opportunities while reducing environmental impact. Choosing certified guides, supporting local businesses, and adhering to Leave No Trace principles are simple yet effective ways visitors can contribute to preserving Mount Kenya’s fragile environment.

Grassroots efforts also play a vital role. The Mount Kenya Trust has positively impacted the lives of 2,000 community members through its collaborative conservation projects [15]. Similarly, the Mt. Kenya Biodiversity Conservation Group distributed 7,400 tree seedlings to schools and communities in 2023 alone [13]. These initiatives empower local communities to protect their environment while fostering a sense of collective responsibility.

The loss of Mount Kenya’s glaciers threatens water supplies, disrupts cultural traditions, and endangers ecosystems. While reversing the retreat is impossible, the dedication of local communities, conservation groups, and responsible travelers provides a glimmer of hope for the mountain’s future. Through collective effort, we can help preserve what remains of this iconic landscape.

Fire and Ice: Mount Kenya’s Lost Glaciers | The New York Times

FAQs

What is causing Mount Kenya’s glaciers to shrink, and how does this affect the environment and nearby communities?

Mount Kenya’s glaciers are disappearing at an alarming rate, driven by climate change. Rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns have accelerated this decline, with experts warning that the glaciers could completely vanish by 2030. Research reveals a staggering 44% reduction in glacial area between 2004 and 2016.

The implications of this loss are far-reaching. Glaciers play a crucial role in supplying water to local communities, supporting agriculture, daily needs, and surrounding ecosystems. Without this meltwater, communities face growing threats of water shortages and food insecurity. Beyond the glaciers, Mount Kenya’s forests are also under threat. Climate change and human activities are expected to cause a significant reduction in vegetation, with estimates suggesting up to 55% of the forest cover could be gone by 2040.

These challenges underline the critical need for conservation efforts to safeguard Mount Kenya’s delicate ecosystems and the people who depend on them.

How have Mount Kenya’s glaciers changed over time, and what does this reveal about climate change?

Mount Kenya’s glaciers have undergone a staggering transformation over the last century, shrinking by about 90% since the early 1900s. The main culprits? Rising temperatures, less cloud cover, and reduced snowfall – factors that have disrupted the glaciers’ ability to replenish themselves.

Scientists warn that these glaciers might vanish entirely by 2030, serving as a sobering symbol of the impact of climate change. Their disappearance doesn’t just underline the warming planet; it also poses serious challenges for water availability and the delicate ecosystems that rely on these ice reserves. It’s a stark call to prioritize action on climate-related issues.

What is being done to protect Mount Kenya’s glaciers, and how can visitors help?

Protecting Mount Kenya’s Glaciers

Efforts to safeguard the shrinking glaciers of Mount Kenya hinge on a combination of reforestation, sustainable farming, and the establishment of protected areas to mitigate climate change’s impact. These measures not only aim to preserve the delicate ecosystem but also improve the lives of nearby communities by promoting sustainable practices.

Visitors play a key role in these conservation efforts through eco-friendly tourism. By choosing sustainable tour operators, minimizing waste, and adhering to park regulations, tourists can make a meaningful difference. Plus, revenue from park fees and tourism directly funds conservation projects, helping to protect Mount Kenya’s glaciers and its unique environment for future generations.